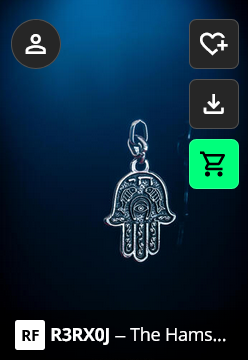

The Hamsa—a palm-shaped amulet with an eye often depicted in its center—stands as one of humanity’s most enduring and cross-cultural protective symbols. While commonly recognized today in jewelry and decorative arts, the Hamsa’s journey spans millennia, civilizations, and religious traditions. This article explores the rich historical tapestry behind this powerful symbol, tracing its evolution from ancient origins to its contemporary global presence.

Prehistoric and Ancient Origins

Paleolithic Hand Symbols (30,000-10,000 BCE)

The human fascination with hand imagery predates written history. Cave paintings from the Upper Paleolithic period, such as those found in France’s Grotte de Gargas and Spain’s Cueva de las Manos, feature numerous hand stencils created by blowing pigment around placed hands. While these early hand images likely carried different meanings from the modern Hamsa, they demonstrate humanity’s ancient connection to hand symbolism as a form of protection, identity, and communication with the divine.

Mesopotamian Precursors (3000-1000 BCE)

Archaeological evidence suggests the earliest direct precursors to the Hamsa emerged in ancient Mesopotamia. Clay amulets shaped like hands have been discovered in archaeological sites dating to approximately 1800 BCE in regions corresponding to modern-day Iraq and Syria. In ancient Mesopotamian cultures, these hand-shaped amulets were associated with the goddess Inanna (later known as Ishtar), who represented fertility, love, and protection.

One notable archaeological find is the “Hand of Ishtar” artifacts, which feature outstretched palms with various inscriptions or decorative elements. These early hand amulets were believed to invoke divine protection against evil forces and negative energies—a core function that would remain consistent throughout the symbol’s evolution.

Ancient Egyptian Connections (2000-1000 BCE)

In ancient Egypt, hand amulets were connected to protective deities, particularly those associated with motherhood and childbirth. The Egyptian “Two Fingers” amulet, representing the fingers used by Isis to help resurrect Osiris, shares conceptual similarities with later Hamsa designs. These early Egyptian hand symbols were often worn to invoke divine protection, particularly for women during childbirth and children during their vulnerable early years.

Classical and Mediterranean Development

Phoenician Influence (1000-300 BCE)

The Phoenicians, master traders of the Mediterranean, played a crucial role in the spread of hand symbolism throughout the region. Their extensive maritime trade networks facilitated cultural exchange between Mesopotamia, Egypt, North Africa, and Southern Europe. Phoenician artifacts featuring protective hand imagery have been found throughout their trading territories, suggesting they were instrumental in disseminating the symbol.

Archaeological evidence from Carthage, a major Phoenician colony in North Africa, includes numerous hand-shaped amulets that bear striking resemblance to the later Hamsa designs. These Carthaginian amulets often featured eyes or geometric patterns within the palm—elements that would become standard in the fully developed Hamsa.

Greco-Roman Period (300 BCE-300 CE)

During the Hellenistic and Roman periods, protective hand symbolism merged with the widespread Mediterranean belief in the “evil eye” (Greek: matiasma; Latin: oculus malus). The concept that malevolent gazes could cause misfortune necessitated protective counter-measures, leading to the increased popularity of apotropaic (evil-averting) symbols.

Hand-shaped amulets from this period often incorporated explicit eye imagery, strengthening the connection between the hand shape and its protective function against malevolent gazes. The Roman “mano pantea” (hand of blessing) and “mano fico” (fig hand) gestures, while different in form from the open palm Hamsa, shared its protective intent and contributed to the Mediterranean tradition of hand-based apotropaic symbols.

Development in Religious Traditions

Jewish Adaptation (200-800 CE)

The Hamsa gained significant traction in Jewish communities throughout the Mediterranean and Middle East during the Talmudic period. As Jewish communities encountered the symbol through interaction with surrounding cultures, they incorporated it into their own protective practices while adapting it to monotheistic principles.

In Jewish tradition, the symbol became known as the “Hand of Miriam,” after Moses’ sister. The earliest Jewish textual references to hand amulets appear in the Talmud, suggesting their use was established by the 5th century CE. These early Jewish Hamsas often featured Hebrew inscriptions, particularly the Shema prayer or other protective verses.

The integration of the Hamsa into Jewish protective practices coincided with the development of Kabbalistic thought, which emphasized divine protection through sacred geometry and Hebrew letterforms. By the early medieval period, the Hamsa had become a standard protective symbol in Jewish communities across North Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Southern Europe.

Islamic Adaptation (700-1200 CE)

Following the rise of Islam, the hand symbol was incorporated into Islamic protective traditions as the “Hand of Fatima,” named after the Prophet Muhammad’s daughter. The earliest Islamic iterations of the Hamsa appear in the Umayyad and Abbasid periods, where the five fingers were increasingly associated with the Five Pillars of Islam and the Prophet’s family.

An important development in the Islamic tradition was the explicit connection between the Hamsa and the concept of khamsa (Arabic for “five”), which refers not only to the five fingers but also carries numerological significance in Islamic mysticism. The number five is associated with protection in numerous Islamic traditions, including the “five holy ones” (Muhammad, Fatima, Ali, Hassan, and Hussein).

Islamic Hamsas from this period often featured Arabic calligraphy, particularly the names of Allah, Muhammad, or verses from the Quran believed to offer protection. The stylistic elements of these early Islamic Hamsas—including geometric patterns and Arabic inscriptions—heavily influenced the symbol’s aesthetic development across cultures.

Convergence in Sephardic and Mizrahi Communities (1200-1600 CE)

The Medieval and Early Modern periods saw a fascinating convergence of Jewish and Islamic Hamsa traditions, particularly in Sephardic Jewish communities in the Iberian Peninsula and later in North Africa and the Ottoman Empire after the 1492 expulsion from Spain.

These communities, living in close proximity with Islamic cultures, developed distinctive Hamsa designs that blend Jewish and Islamic aesthetic elements. Artifacts from this period often feature Hebrew prayers alongside Arabic-inspired decorative motifs, demonstrating the cross-cultural nature of the symbol.

The Hamsa became especially prominent in amulets designed to protect homes, with larger versions often mounted by doorways. Manuscript illuminations and ceremonial objects from Sephardic and Mizrahi communities frequently incorporated the Hamsa, cementing its place in Jewish visual culture.

Colonial Era and Global Spread

North African Developments (1600-1900)

During the Ottoman period, North Africa emerged as a particularly important center for Hamsa production and innovation. In Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, and Libya, Jewish and Muslim artisans created increasingly elaborate Hamsa designs, often incorporating local artistic traditions.

Moroccan Hamsas, in particular, developed distinctive characteristics, featuring intricate filigree work, colorful enamel inlays, and complex geometric patterns. These North African designs would later have significant influence on global perceptions of the Hamsa, particularly as North African Jews emigrated to Israel, Europe, and the Americas in the 20th century.

Colonial Encounters and Ethnographic Documentation

European colonial presence in North Africa and the Middle East led to increased Western awareness of the Hamsa. Early ethnographers and anthropologists documented the symbol’s use across different communities, though often through a colonial lens that exoticized these protective practices.

Collections of “Oriental” artifacts brought to European museums frequently included Hamsas, introducing the symbol to Western audiences, albeit often without appropriate cultural context. This period saw the first academic studies of the Hamsa, though these early works frequently misinterpreted or oversimplified its cultural significance.

Modern Revival and Global Adoption

Israeli Adoption and Secularization (1948-Present)

The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and subsequent immigration of Jewish communities from across the Middle East and North Africa brought diverse Hamsa traditions together. Initially viewed with some ambivalence by the European-dominated Israeli establishment as a symbol of “Oriental superstition,” the Hamsa gradually gained acceptance as part of Israel’s multicultural heritage.

By the 1970s, the Hamsa had experienced a significant revival in Israeli popular culture, appearing in both religious and secular contexts. Israeli artists began creating contemporary interpretations of the symbol, often blending traditional motifs with modern artistic sensibilities. This revival coincided with increased pride in Mizrahi heritage and cultural traditions within Israeli society.

New Age Adoption and Global Spread (1970s-Present)

The late 20th century saw the Hamsa adopted by New Age spiritual movements, particularly in North America and Europe. Divorced from its specific religious contexts, the symbol was embraced as a universal protective emblem and incorporated into the eclectic spiritual iconography of the New Age movement.

This period also saw the Hamsa’s entry into global fashion and decorative arts. Designer jewelry featuring the symbol became popular beyond Middle Eastern and North African communities, introducing the Hamsa to new audiences worldwide.

Contemporary Multicultural Symbol

Today, the Hamsa exists simultaneously as:

- A religious symbol with specific meanings in Jewish, Islamic, and Christian contexts

- A cultural emblem representing Middle Eastern and North African heritage

- A fashionable decorative motif in global popular culture

- A spiritual symbol embraced by various New Age and eclectic spiritual practices

This multilayered existence reflects the Hamsa’s remarkable adaptability across time, cultures, and belief systems, while maintaining its core function as a protective symbol.

Archaeological Evidence and Material Culture

Notable Archaeological Finds

Archaeological evidence of the Hamsa’s development includes:

- Clay hand amulets from Bronze Age Mesopotamian sites (circa 1800 BCE)

- Carthaginian hand-shaped pendants with palm designs (500-300 BCE)

- Roman-era glass and metal hand amulets from sites throughout the Mediterranean

- Medieval Jewish hand amulets with Hebrew inscriptions from Cairo Geniza documents

- Ottoman-era metal Hamsas with intricate filigree work

These artifacts demonstrate the symbol’s continuous presence and evolution across multiple civilizations.

Artistic Evolution

The Hamsa’s artistic development shows distinctive regional variations:

- North African Hamsas: Typically feature bright colors, intricate filigree work, and often incorporate fish symbols for additional protection

- Ottoman Hamsas: Usually display elaborate calligraphy and geometric patterns

- Yemenite Jewish Hamsas: Characterized by distinctive silverwork techniques and often incorporate biblical verses

- Contemporary Israeli Hamsas: Range from traditional designs to modern artistic interpretations

These regional variations reflect how the symbol has been adapted to local artistic traditions while maintaining its essential form and function.

Cultural Anthropology and Lived Traditions

Protective Practices

Anthropological studies document diverse uses of the Hamsa in daily life:

- Hanging in homes, particularly near entrances or in newborn babies’ rooms

- Worn as jewelry, especially by women during pregnancy or by children

- Incorporated into wedding decorations to protect the new union

- Included in business establishments to ensure prosperity and ward off envy

These protective practices often cross religious boundaries in regions where different faiths share cultural traditions related to protection against the evil eye.

Contemporary Cultural Significance

Today, the Hamsa holds different but overlapping meanings for various groups:

- For Jews of Middle Eastern and North African descent, it represents both religious protection and cultural heritage

- For Muslim communities, particularly in North Africa, it connects to both Islamic tradition and regional cultural identity

- For diaspora communities, it often serves as an emblem of cultural roots and traditional values

- For many global consumers, it represents a fashionable symbol with exotic appeal and spiritual connotations

These varied interpretations demonstrate the symbol’s remarkable ability to carry multiple meanings simultaneously.

Conclusion: The Hamsa’s Enduring Legacy

The Hamsa’s journey from ancient Mesopotamian fertility amulet to global protective symbol illustrates the complex ways religious and cultural symbols evolve across time and space. Its persistence across millennia and adaptation across religious traditions speaks to the universal human desire for protection against malevolent forces.

What makes the Hamsa particularly remarkable is its ability to maintain its core protective function while adapting to diverse cultural contexts. Few symbols have demonstrated such cross-cultural appeal while retaining their essential meaning and purpose.

As the Hamsa continues its journey into the 21st century, it serves as a powerful reminder of humanity’s shared cultural heritage and the universal human impulse to seek protection through symbolic means. Whether worn as religious protection, cultural identifier, fashion statement, or spiritual talisman, the Hamsa’s open palm continues to offer its blessing to an increasingly interconnected world.